Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

Pascal's Principle

In Lesson 1 of this chapter, we explored properties of ideal fluids. One of these properties is that ideal fluids are incompressible. That means that even under great pressure, the fluid will maintain the same volume. We said that no real fluid is perfectly incompressible, just like no ramp is perfectly frictionless. There are many fluids (like water), however, that are very close to being incompressible.

In the previous section of this lesson, we also learned that the deeper we go in a fluid, the greater the pressure. This is because at a greater depth, there is a greater weight of fluid above us. You experience this when you swim to the bottom of a pool. This is also why water towers are designed to hold water at a height greater than the surrounding homes. We can turn on a faucet and, because the pipes in our homes are below the height of the water tower, this increased water pressure will force the water out.

As a result of both the incompressibility of fluids and the fact that pressure increases with depth, it follows that any change in pressure in one part of this fluid will be transmitted undiminished to all other parts of the fluid. This means that if the pressure at the top of a water tower were increased by 50 units of pressure, the water pressure in every part of the pipes throughout the neighborhood would also increase by 50 units of pressure. This significant concept was first recognized by the French scientist Blaise Pascal. To give him credit, we refer to this as Pascal’s Principle.

Imagine filling a U-shaped tube with water. According to our pressure-depth equation from earlier in this lesson, the pressure at the top of the water on both sides of the tube will be the same since the water is at the same height. Now, let’s put a piston (a plug that can seal but can move) on both the left and right sides to cap the water. If we increase the pressure on the left side, the pressure on the right side must also increase instantaneously. That’s what Pascal’s Principle tells us. And if the water remains at the same height, the force pushing down on the left side will result in an identical force pushing up on the right side, provided that the areas of the two pistons are the same. While this might not seem like a big deal, what comes next is where things get interesting.

Now, imagine that we replace the right side of the U-shaped tube with a much wider mouth opening. It remains true that an increase in pressure at one point in the fluid will result in an equal increase in pressure at every point in the fluid. So, if the pressure on the left side was increased by 50 Pa, the pressure on the right side would also increase by 50 Pa. And if the water remains at the same height on each side, both sides will continue to be at the same pressure as each other. On the left side, this pressure results from a relatively small force pushing down over a relatively small area. To achieve the same pressure on the right side, however, the water will exert a much greater total force since it is pushing up over a larger area. Notice that while the pressures on each side of the tube are the same, the forces are not.

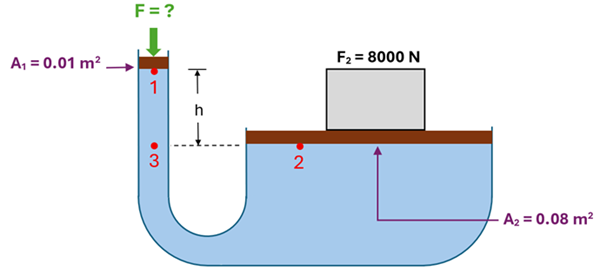

As an example, consider the situation below. A 1000 N weight can lift an 8000 N weight since the water pushing up on the 8000 N weight is pushing over an area eight times greater. This result, which follows from Pascal’s Principle, is very significant. This concept is the basis for many practical applications involving fluids. In Example 2, we’ll see that this is the principle behind a hydraulic lift.

Since the pressure at the top of the water on both sides is the same (since they are at the same height), we can say that the ratio of the force/area on both sides must be equal. We might summarize these results in a mathematical equation that we’ll call Pascal’s Equation:

It should be noted that this equation assumes that the height of the fluid on the left side is the same as the height of the fluid on the right side. Later in this section, we’ll make a simple modification to this equation that considers the case where the fluid on the left is at a different height than it is on the right. For now, however, let’s consider a couple of example where we get to apply Pascal’s Principle and Pascal’s Equation.

Example 1: Pressure Changes

Problem: On a typical day (atmospheric pressure = 1.00 atm), the absolute pressure at a depth of one meter in a pool of water is approximately 1.10 atm. As a storm approaches, the air pressure above the pool drops to 0.97 atm. What is the absolute pressure at this depth in the pool now?

Solution: According to Pascal’s Principle, any change in pressure in one part of this fluid will be transmitted undiminished to all other parts of the fluid. As a result, if the pressure at the surface of the water decreases from 1.00 atm to 0.97 atm, the absolute pressure at a depth of one meter will decrease from 1.10 atm to 1.07 atm. In other words, the decrease of 0.03 atm of pressure at the surface results in a decrease of 0.03 atm throughout the fluid.

Example 2: Hydraulic Lifts

Problem: A mechanic needs to lift a car to service it. He uses a hydraulic lift filled with hydraulic fluid for this purpose. The lift consists of a circular tube with a diameter of 0.080 m and a hand piston that the mechanic can push down. The car is on its own circular piston, with a diameter of 1.20 m. What force will the mechanic need to exert to lift a 15,000 N car? Ignore the weight of the pistons and any frictional forces.

Solution: Using Pascal’s Equation, we see that the force the mechanic must exert to lift the car is only 66.7 Newtons. This is significantly less than the car's weight. This is why hydraulic lifts are so useful. Note that, since the diameter of each piston was given, its cross-sectional area can be found using A = π r². Recall also that the radius is half the diameter.

Are We Getting Something for Nothing?

“Wait a minute!” you might be thinking. “Aren’t we getting something for nothing?” After all, is it possible for a person to exert a very small force and lift a very heavy object? Doesn’t this contradict the conservation of energy? A small force can lift a very heavy object without contradicting the conservation of energy. We’ve actually seen this happen with a simple machine, such as a lever.

Consider a person trying to lift a very heavy rock. By using a board (a lever) that can pivot about a point close to the rock, the person can exert a small force to lift a heavy object. The ‘catch’ comes as we notice that the person has to push the board down a very large distance, even though the rock is raised only a small distance. Recalling the concept of work (work = force • distance), we see that the work done by the person is equal to the work done in lifting the rock. Said another way, the energy the person put into this is equal to the energy required to lift the rock. Thus, we see that the principle of conservation of energy remains valid.

The same is true for the hydraulic lift in Example 2. While the mechanic pushed down with a much smaller force than the weight of the car, he would have had to push down over a much greater distance than the height the car was raised. That’s why a mechanic has to pump the hydraulic arm many, many times to lift the car even a small height.

Example 3: Energy in Hydraulic Lifts

Problem: Consider the situation in Example 2 with a mechanic lifting a 15,000 N car with only 66 N of force (rounded down from 66.7 for convenience).

(a) If the mechanic wanted to lift the car 2.0 m high, through what distance would he need to move the left piston?

(b) If the mechanic moves the hand piston 0.50 m during each pump, how many pumps would be required? (Assume that the height of the fluid remains the same on each side and that frictional forces can be ignored).

Solution: (a) Since the work needed to lift the car is Wcar = 15,000 N • 2.0 m = 30,000 Joules, the mechanic must do 30,000 Joules of work. Thus, Wmechanic = 30,000 J = 66 N • d. We find that d = 455 m! (b) If each pump of the piston moves through a distance of half a meter, the mechanic will need to pump the piston 910 times!

Pascal's Equation & Different Height Pistons

Our study of Pascal’s Equation above assumed that the height of the fluid (and thus the piston in a hydraulic lift) was the same on each side. In practice, this will not always be the case. How would we modify Pascal’s Equation to take this height difference into consideration?

Let’s revisit the situation we considered earlier, where a 1000 N force applied to an area of 0.01 m2 was able to supply an 8000 N force over an area of 0.08 m2. This worked because the pressure at the surface of the two sides was the same (since they were at the same height). But what if the height of the fluid on the left is higher than that on the right? Would more force or less force be required to lift the 8000 N weight?

To answer this question, let’s consider something that we know to be true from the previous section:

Equal depths in the same fluid will be at equal pressures

Using this result, we know that the pressure at 2 and 3 must be the same since they are at the same height. While 2 is at the top surface of the fluid on the right, 3 is at a depth ‘h’ from the surface of the fluid on the left. Thus, the pressure at 1 will be less than the pressure at 3 (which is the same as the pressure at 2). The amount less can be found using the pressure-depth equation (P2 = P1 + ρ g h) from our last section. Solving this equation for P1 and recalling that P = F/A, we can write,

If we consider point 1 to be 2.0 m above point 3 and the fluid is water (which has a density of 1000 kg/m3), we find the force required at 1 is now 804 N (less than the 1000 N required when they were at the same height).

Although this calculation may appear somewhat involved, the result should make sense. We notice that the force required now is 196 N less than what it was when the water on the right was at the same height as that on the left. Why 196 N? It turns out that this is just the weight of the water between points 1 and 3. In other words, this ‘extra’ water already exerts a downward force of 196 N on the water at point 3. Therefore, only 804 N of additional force is required to reach the 1000 N force that we found earlier.

Example 4: Weight of Water

Problem: Show that the weight of the ‘extra’ water in the left column between heights 1 and 3 is 196 N.

Solution: Since the weight of any object is its mass times the acceleration of gravity (weight = m g), we can find the weight of this water if we first determine its mass. Since mass = density times volume, the mass of the water in this column will be m = ρ V = ρ (A•h), where A is the area and h is the height of this column of water. Performing these calculations, we indeed see that the weight of this water is 196 N.

Example 5: Hydraulic Lift Revisited

Problem: A 300 N force is applied to the left side of a hydraulic lift of area 0.1 m2. The lift is used to raise a heavy weight using a piston of area 1.0 m2. The left piston is 0.40 m above the right piston and the density of the hydraulic fluid is 800 kg/m3. What weight can this hydraulic lift support?

Solution: Using Pascal’s Equation for different heights, we find the unknown weight to be approximately 6163 N.

Check Your Understanding

Use the following questions to assess your understanding. Tap the Check Answer buttons when ready.

1. A water-filled lift uses a small 50 N weight to exactly support the large weight on the right. The left piston has an area of A, while the right piston has an area of 20A. The two pistons are at the same height.

(A) What is the weight lifted on the right side?

(B) If the water were replaced with oil, which has a lower density than water, would your answer be greater, less, or the same?

2. If the pressure in a hydraulic press is increased by 1000 N/m2, how much extra weight will the output piston support if its cross-sectional area is

(A) 1 m2

(B) 2 m2

(C) 0.5 m2

3. A barber’s chair with a person in it weighs 1944 N. The output piston of a hydraulic system lifts the chair when the barber’s foot supplies a 24 N force to the input piston. Assume the two pistons are at the same height.

(A) What is the ratio of the area of the output piston to that of the input piston?

(B) If each piston is a cylinder (with circular cross-section), what is the ratio of the output piston’s radius to that of the input piston?

4. The hydraulic lift below is similar to that shown in Problem 1 above, except that the left piston is at a higher height.

(A) The equal height system (Problem 1) could support a weight of 1000 N. Will this different height system be able to support more than 1000 N, less than 1000 N, or exactly 1000 N?

(B) If the water were replaced with oil, which has a lower density than water, would your answer to Part A change?

Looking for additional practice? Check out the CalcPad for additional practice problems.